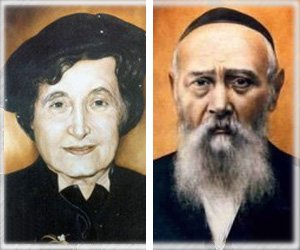

The most recent Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, became the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, the seventh link in the dynasty. It is important to have some idea of the particular atmosphere in which this phenomenal, incomparable person was raised and educated. We will try to describe his father's home - the family, the circumstances, and the events that surrounded it.

In 1917, the year of the Bolshevik revolution, the world was caught up in a wave of unprecedented enthusiasm. Revolutionary slogans, translated into numerous languages, were galvanizing people's imagination. Thousands of mouths were screaming in mindless frenzy: "Friendship among nations!" and "Proletariat of all countries, unite!" The blue of the sky seemed to be obscured and eclipsed by the blood red of the banners. The sad irony lay in the fact that the majority of top Bolshevik leaders and torchbearers were Jewish by birth. They waged a campaign of vilification and brutality against religion - and that primarily meant, of course, the ancient religion of their fathers, which they had betrayed. These people were responsible for portraying religion as one of the main enemies of revolution. It took very little time for the population of the former Russian empire to realize that the lawlessness and cruelty of the czarist regime paled before the ruthless brutality of the Bolsheviks. The savagery of the special police, the death sentences pronounced by the troikas (groups of three Secret Police) and summarily carried out, the growing number of people dragged from their homes never to be seen again - all convinced the people that resistance was useless, that "even the walls have ears," that not only their words but even seditious thoughts would be swiftly and surely punished.

To be sure, the Jewish religion was not the only one to suffer. Bolshevik repression was directed equally against Christian priests and worshippers. This prompted the Pope to issue a firm protest. Russia's new dictatorial regime, in its merciless policy of terror, lost no time in learning the art of disinformation. One of its replies to the Pope and world opinion was to stage a showcase conference of Byelorussia's rabbis, scheduled for the beginning of 1928 in Minsk. It was the government's intention to have thirty-two of the rabbis attending the conference sign a declaration denying the existence of any anti-religious persecution and countering all the allegations.

With broken hearts and shaking hands, the rabbis signed the declaration prepared beforehand. In triumph, the government began to plan another conference, this one to be attended by rabbis from the Ukraine. The conference was to be held in Kharkov, then the Ukrainian capital. There was only one obstacle. According to government informers, the rabbi of Yekaterinoslav (later renamed Dnepropetrovsk), Levi Yitzchak Schneerson (a great-grandson of the Tzemach Tzedek, and an immensely popular and respected figure among the Jews), adamantly refused to sign the fabricated statement. The GPU (State Political Directorate), as the secret police had come to be called, decided to summon Rabbi Schneerson for a little talk. Everything was done to make this a "congenial" affair, with not a single threat or accusation against the rabbi. The mouths of the GPU officials were all but dripping with honey. Their boss delivered a lengthy speech to the effect that he had no doubt that the esteemed rabbi would sign the statement rebuffing the vile insinuations of international capitalism, and the Pope in particular, concerning anti-religious measures allegedly taking place in the Soviet Union. He went on to say that Jews must be grateful to the Soviet regime, which had freed them from the czarist yoke. Finally, he promised that Jews would be awarded a series of concessions provided the statement was signed. "Of course," he added with an insidious smile, "if the statement is not signed, you and other conference participants may be in for some trouble."

The rabbi had already risen to take his leave, when one of the GPU officials pulled a train ticket from a desk drawer. "We have thought of everything," he said. "Here is your ticket to Kharkov. First class, of course."

However, Rabbi Schneerson's reply was brusque and definite: "I have no need for your ticket. I will come to the conference at my own expense." He left without saying another word.

On the appointed day, the rabbi arrived at the conference. There were several dozen rabbis in the auditorium. Scurrying among them were some unfamiliar characters easily recognizable as GPU agents. Palpable fear and tension were in the air; the participants avoided talking to one another. One by one, they were called to the podium, where they recited the prepared texts and, hanging their heads in shame, returned to their seats. When it was Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson's turn, a barely audible rustle went through the auditorium, followed by total silence. With quick and confident steps, the rabbi crossed the floor, climbed up to the stage and, in a loud and clear voice, called upon everyone present not to sign the statement, calling it an outright fabrication. "Those who sign this lie will be committing a grave transgression," he concluded his brief speech.

Deep silence descended on the auditorium. To the utter astonishment of all those present, no one came up to Rabbi Schneerson to demand that he retract his words. The conference lasted for several more days, during which Rabbi Schneerson was able to repeat his appeal a number of times. His words and his unshakeable conviction were beginning to affect those attending the conference, and their spirits were regaining power.

Seeing their plans threatened, the authorities summoned Rabbi Schneerson to a meeting with the people's commissar in charge of education in the Ukraine. The commissar attempted to gain the rabbi's sympathy with a show of mildness and friendliness. However, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak explained, patiently and without the slightest sign of fear, that nothing would intimidate him into signing the declaration, which did not contain a single word of truth.

"You persecute religion every way you can," he said. "You destroy synagogues and yeshivot, close down printing houses and ritual baths, deprive us of our legal right to lead Jewish lives. Do you really believe that I can be forced to sign this fabrication?"

At this point, the commissar could no longer restrain himself. "I'll have you know," he yelled, "that we will not tolerate your incitement! You are undermining the foundations of the Soviet regime, and you will pay dearly for this!"

The authorities never did obtain the desired results from the rabbinical conference. They were literally fuming with rage, which grew even more intense when they found out that someone had managed to smuggle information about these events abroad, triggering a storm of reactions and protests throughout the world. Thousands of Jews inside and outside the Soviet Union held their breath: the solitary battle of one seemingly defenseless Jew against an all-powerful state had an unreal quality.

This was not the only clash between Rabbi Levi Yitzchak and the Soviet state. That same year, the government conducted a population census. One of the items in the questionnaire read, "Are you religious or non-religious?" It was common knowledge that anyone who admitted his religious affiliation would expose himself to various perils and repressive measures. Many ordinary religious Jews saw nothing wrong with registering as non-religious; after all, they did it solely out of fear of the authorities and the desire to avoid persecution.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, on the other hand, thought differently. He gathered his followers in a synagogue, and announced that registering as non-religious would be tantamount to apostasy and a grave transgression. There could be no two ways about it! Despite the enormous fear of the authorities, the words of someone like Rabbi Levi Yitzchak could not be ignored, and many people abided by his instructions. Naturally, the GPU added this information to his "file."

Many other events in the life of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson guide adults and children to this day. The Rebbe related the following episode to children during a gathering in honor of his father's birthday. The Rebbe explained that the story he was about to tell had not become widely known for various reasons. This story illustrates what a Jew who puts the observance of Torah commandments above all else can achieve. "The story I am about to tell you," began the Rebbe, "is about flour and matzah for the Pesach holiday."

My father, one of the most prominent rabbis in Russia, was the rabbi of Yekaterinoslav, one of the largest cities of the Ukraine, in an area that supplied wheat to the entire Ukraine. Thus it was natural that people turned to him to certify the kashrut of Pesach flour. Obtaining a kashrut certificate from my father was not an easy matter. He would dispatch reliable people to every mill that supplied Pesach flour. Their task was to observe the production to make sure that the grain did not come into contact with water or any other moisture. Whenever this did happen, they would immediately pronounce the flour not kosher for Pesach. Everyone knew that attempts to appeal to my father's leniency were totally useless. When the Soviet government took control of all means of production in the country, including the mills and bakeries, envoys from a number of Jewish communities approached my father in an attempt to convince him that under the circumstances, it was extremely dangerous for Jews to refuse to purchase flour from the government. In those years, during Pesach the overwhelming majority of Jews only used matzah. Since matzah flour was much more expensive, pronouncing it not kosher would cause considerable financial loss to the government, the only source. The authorities would surely react with savage vengeance if this were to happen.

"I will certainly issue kashrut certificates," My father replied, "provided I am allowed to send supervisors to each mill, and provided the authorities agree to accept their instructions unconditionally. If, however, the government refuses, then issuing kashrut certificates would be out of the question. Moreover," my father continued, "If the government does not agree to my terms, I will do everything in my power to inform every Jew that the matzah flour was not made under my supervision, and is therefore not kosher for Pesach."

The envoys told my father that he would probably be allowed to send his observers, and if they labeled the flour as kosher, everything would be fine. If, however, they had any reservations as to whether everything was done in accordance with Torah commandments, and if my father refused to approve the flour as a result, that would amount to an open challenge to the Soviet government, with all that implied.

"In that case," my father said, "I will go to Moscow to see the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, to explain that it is impossible for me to issue false kashrut certificates." If the authorities decided to punish him, he was ready for that. This would be far preferable to even thinking about the possibility of violating the laws of Torah as decreed by the Almighty!

The envoys were flabbergasted. They could not fathom how one seemingly powerless Jew could dare make an open and adamant stand against the omnipotent regime. They made another attempt to reason with father and "bring him to his senses," but to no avail, as was to be expected.

Eventually the entire affair reached Kalinin, the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, who was known to have retained at least some semblance of humanity, in contrast to the other communist leaders. Kalinin, evidently impressed by the rabbi's courage, instructed the managers of the mills to unconditionally accept my father's demands.

This was nothing short of a miracle. The authorities had yielded to the demands of a Jew, a rabbi! That year, and for many years after that, Pesach matzah was baked in full conformance with the laws of kashrut.

"And so," the Rebbe concluded his story, "we see that when a proud Jew stands firm and does not give in even when facing the Soviet government, which may appear all-powerful to many, ultimately such a Jew will triumph. All of this should be a reminder to each of us, especially to children. We must realize that our duty is to adhere firmly to the views and laws of Torah. This firm stand is based on the fact that the words of Torah were dictated by the Almighty Himself, who created heaven and earth - and it is unthinkable for a Jew to act contrary to the words of Torah. Once we embrace this truth and act accordingly, we will achieve our goals, even if they are directly opposed by a mighty state. After all, the entire universe was created in accordance with Torah, and nothing in this universe can possibly contradict its laws. Moreover, just as the authorities in this story issued orders to bake matzah in accordance with the Shulchan Aruch, the Code of Jewish Law, so too, any gentile, seeing a Jew who proudly follows the path of the Lord, becomes in fact a 'tool' in G*d's hands."

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak exhibited courage not only in critical moments or in confrontations with the Soviet regime. Ineveryday life, full of hardship and danger, his sole concern was for Jews and Judaism. This concern was manifested in many situations: when it was time to circumcise a baby whose parents worked for the government, and performing the circumcision ceremony required heroic effort; when a Jew with no family was on his deathbed; when complex halachic issues arose concerning practical application of Torah laws; when a Jew needed support, either material or spiritual. Anyone who needed help could turn to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, day or night, and he was always there to lend a helping hand through word or deed.

His capacity for self-sacrifice knew no bounds. At one time he entertained thoughts of leaving the Soviet Union and escaping the unbearable perils and privations of its totalitarian regime. Yet he cast away these thoughts, refusing to leave his community. He was fully aware that the survival of his own Jewish community, and perhaps of all the Jewish communities in the Ukraine, would be impossible without his presence. If he were gone, who would lead the struggle for kosher food, Jewish education, or the continued functioning of mikvaot, without which it would be impossible to observe the laws of family purity? For that reason, he did not even reply to a letter signed by Jerusalem rabbis offering him a rabbinic position. According to the recollections of his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, there was another reason for his failure to reply: Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was convinced that he did not deserve the privilege of living in the Holy Land. Even though invitations from Israel continued to arrive during the subsequent years, he chose to remain in the Soviet Union, together with his community.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak served as the rabbi of Yekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk) for thirty-nine years before his arrest, which marked the beginning of years of suffering and privation. On the night of the 10th of Nisan, 5699 (1939), the long arm of the Soviet regime reached Rabbi Levi Yitzchak. At three a.m. there was a knock on the door. The Rebbetzin opened it and saw four officers of the NKVD (Soviet internal security). Pushing the Rebbetzin aside, the officers burst into the house, shouting, "Where is the rabbi?"

When the rabbi came to meet the unwelcome guests, the chief officer produced the search and arrest warrant. The search began immediately. The officers smashed the doors of bookcases, piling hundreds of volumes onto the floor. They were particularly interested in letters and manuscripts. The rabbi's personal correspondence, including numerous letters from the Joint Distribution Committee, and his rabbinical diploma, were confiscated. The most valuable books and manuscripts were sealed with wax. Among the latter was a manuscript on Chassidism written by the Tzemach Tzedek himself, including a marginal note written by the Alter Rebbe on one of the pages. The manuscripts of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak himself were packed separately.

Around six a.m., after turning the entire house upside down, they ordered the rabbi to get dressed and come with them. His sole request was to be allowed to bring along a small package of matzah, for the Pesach holiday was only a few days away. To his surprise, the NKVD officers granted his request.

The Rebbetzin strove to understand what had happened, reconstructing in her mind the events that preceded the arrest. Gradually, certain things began to make sense. For example, she realized why two suspicious young men had been lurking around their home for close to a month. Three weeks before the arrest, on Purim, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak had hosted a large gathering. He had delivered a long speech about the significance of Purim and its moral relevance to the present. The gathering had culminated in intense Chassidic dancing which wordlessly expressed the people's fears and hopes. At the end, the guests dispersed, unaware of the NKVD agents who had been watching their every move. Meetings of this kind were strictly forbidden, and the Rebbetzin suspected that the Purim gathering would be used as evidence against her husband.

Driven to the verge of total despair by the lack of any news of her husband's fate, the Rebbetzin suddenly received a message: the rabbi was being kept in the local prison. She was also informed that once every ten days he was allowed to receive a food parcel. The next day for sending a parcel was a Saturday, and the Rebbetzin asked a young gentile woman she knew to take it to the prison. The next time, the Rebbetzin had to wait for almost twelve hours before the prison authorities accepted the parcel. Finally, when it had grown totally dark outside, one of the guards informed her that she had a note from her husband. In this note, he told her, among other things, that the previous parcel had never reached him, since he had refused to sign the receipt for it on Shabbat.

As it turned out, one of the charges against Rabbi Levi Yitzchak had to do with his leading role in the construction of a mikveh. There were a series of other charges concerning his alleged contacts with "hostile elements." Foremost among these "hostile elements" was his son's father-in-law, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, who had left the Soviet Union long before, but who was still bitterly hated by the Bolshevik regime.

The NKVD butchers had broken the spirit of countless thousands of young, healthy prisoners, forcing them to sign "remorseful confessions" admitting to "crimes" concocted by their interrogators. A released convict told the Rebbetzin that Rabbi Levi Yitzchak had spent thirty-two days in solitary confinement under inhuman conditions, and that the prison guards were relentless in inventing new forms of torture and abuse. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, who was sixty at the time, remained steadfast, and he triumphed over every torture, physical and spiritual. His human and Jewish pride and his indomitable spirit and faith served him in good stead. Rumors about him circulated within the prison system; he was becoming a legendary figure.

Almost a year of perpetual, agonizing anxiety about the rabbi's health and life had passed since the day of the arrest. Using every roundabout way available, the Rebbetzin managed to learn that the rabbi's trial would be held in Moscow. She went there and made superhuman efforts to arrange a visit with her husband. For a long time, her attempts bore no fruit. She did manage to find out that her husband was alive and sentenced to a five-year exile in a remote area with no Jewish population. Finally, she was to be allowed one visit before his departure.

Initially, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak was transferred back to the Dnepropetrovsk prison; then he was held in a Kharkov jailhouse. His health was deteriorating with every passing day. Finally, the rabbi was sent into exile without ever being told where exactly he was going. The journey seemed endless and was full of misery. For eleven days the prisoners were issued one glass of water a day. People greedily gulped down the water to partially quench their terrible thirst. Yet Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, whose spirit always prevailed over his physical needs, allowed himself no more than a couple of swallows, saving the rest of the water for ablutions, without which he could not recite the prayers.

Finally, the train arrived in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan. From there, the prisoners were dispatched to Chiili, a town already filled with political exiles. The NKVD thugs had astutely surmised that living in a place like Chiili would be the worst punishment for Rabbi Levi Yitzchak. In addition, the living conditions in Chiili were appalling. The swampy ground exuded heavy moisture into the air. Swarms of mosquitoes were a constant source of irritation. The huts of mud-covered wood were no protection against the murderous climate. Epidemics were rampant. Hunger was ever-present; even drinking water could only be obtained with considerable difficulty. Here the rabbi would be completely cut off from his family and his people for an indeterminate period of time. For the rabbi, this was worse than any physical hardship.

When the Rebbetzin' s desperate attempts to obtain a pardon for her husband ended in failure, she went to join him in Chiili. If the lonely battle with the hardships of everyday life required feats of courage, observing the Jewish holidays became an act of self-abnegation. It was especially difficult to comply with all the intricate laws of Pesach. Despite everything, the Schneersons were fully committed to making any sacrifice necessary, creating a holiday atmosphere around them.

Time passed without bringing any relief. When he became gravely ill, his Rebbetzin devoted herself heart and soul to easing his plight and enabling him to continue his Torah studies and writing. She would stand in endless food lines, or walk for miles in order to settle some problem with a boorish government official - all in order to protect her husband.

One account of the Rebbetzin's life in exile recalls the dignity with which she faced hardship and hunger. She would often give the last piece of bread to a hungry guest without the slightest hint that the household was in dire need, or that this was literally their last morsel, and that there was no hope of getting more bread the next day.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak spent days and nights studying Torah. Naturally, he dreamed of recording his thoughts and revelations, but paper and ink were very scarce. The Rebbetzin would walk to the fields to gather plants, and steep them in water to make thick ink, which Rabbi Levi Yitzchak used to write down his thoughts. He did much of his writing in the margins of the books he was studying. Due to the lack of ink and paper, his writing was very concise.

Keeping and smuggling written records was extremely dangerous, and people had been known to disappear without a trace for far lesser "transgressions." Nevertheless, the Rebbetzin, who had devoted her entire life to her husband, kept the manuscripts after he left this world; the Jewish world was enriched by the work of the late Rabbi Levi Yitzchak solely through her efforts. The exiles suffered from heat in the summer, from bitter cold in the winter and from severe hunger all year. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's health continued to deteriorate. He contracted a severe case of malaria, and barely managed to recover; a gentile doctor among the exiles secretly treated the rabbi.

Amidst the spell of misfortune and deprivation, the Schneersons received unexpected moral support in the form of a telegram from Europe, sent by their eldest son, Menachem Mendel, who later became the Rebbe. Several days later a food parcel arrived from him.

Years went by. The endurance and courage of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak appeared to be infinite. A number of people in the center of the country continued to endanger their lives and freedom in order to bring about the rabbi's release. Finally he was released, settling in Alma Ata. On the 20th of Av, 5704 (1944), Rabbi Schneerson left this world. The few Jews who lived in that city did not leave his side until the very end. Jews still come to Alma Ata from Russia and other countries to Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's grave to ask the rabbi to intercede on their behalf in the higher realms. They have amazing stories to tell about the help and blessings that the tzaddik obtained for them from the Almighty.

|