Chabad differed from the other Chassidic movements from its very inception. Although the teachings of Chabad are based on the rational concepts of Chochmah (reason), Binah (understanding), and Da'af (knowledge), the biography of Chabad's founder, Rabbi Shneur Zalman, is cloaked in mystery; his very birth was accompanied by supernatural portents. According to Chassidism, most of the souls that descend to our material world are sent from heaven to correct sins they committed during their past incarnations. Only in rare cases does the Almighty send down a new soul - exalted, pure, unblemished - entrusted with a special mission for the benefit of the Jewish people. Such was the soul of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, and the Baal Shem Tov knew of its impending arrival, as well as its appointed task: to pave the way for the coming of Mashiach. For reasons known to the Besht alone, he played almost no direct role in raising and educating the boy. Moreover, he forbid Shneur Zalman's father, Rabbi Baruch, to take the boy along on his annual pilgrimage to the Besht in Medzhibozh. The Baal Shem Tov mentioned Shneur Zalman on only one occasion. "He is not destined to be my pupil. His teacher will be the one who comes after me."

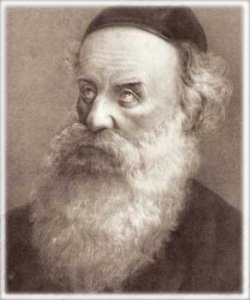

Rabbi Shneur Zalman was born in 1745 in Liozna (situated in the Vitebsk area of Byelorussia). He married at fifteen, and following his marriage, Shneur Zalman joined his father-in-law in Vitebsk. Before long, however, he decided to leave his home in search of a deeper understanding of Torah. He had already learned everything that Vitebsk could offer him. At that time, a young man eager to devote himself to Torah study would usually go to the great city of Vilna, to the Gaon's academy. It is thus not surprising that when Rabbi Shneur Zalman decided to go to Mezherich instead, his father-in-law, a "Litvak" (a common name for residents of historical Lithuania, what is now Lithuania and Byelorussia, most of whom were mitnagdim), was deeply disappointed and frustrated. In his anger, he withdrew all financial support from the young couple. This, however, did not stop Rabbi Shneur Zalman and his young wife. They were firmly convinced that they were on the right path, and that the Almighty would not abandon them. Promising to return in a year and a half, Rabbi Shneur Zalman set out on his journey.

Eventually he reached Mezherich and Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid. His initial impression was not very encouraging. The Maggid and his circle failed to meet his expectations. The prayers, and the rituals that preceded them, seemed excessively long, taking up the time he had intended to devote to study. Increasingly, he believed that he had made a wrong decision. Eventually, he resolved to go back to Vitebsk.

However, heaven had a different plan. Shortly after leaving Mezherich, Rabbi Shneur Zalman remembered that he had forgotten something at the synagogue. As he returned to the synagogue, he saw Rabbi Dov Ber surrounded by his disciples. He listened, realized that they were discussing a highly complex halachic issue, came closer, and found himself unable to leave. The profound, elegant and insightful analysis provided by the teacher literally entranced him, and all his earlier misgivings vanished without a trace.

In Mezherich, Rabbi Shneur Zalman developed the central tenets of his philosophy. He was particularly drawn to three fundamental principles: that the human mind, no matter how exalted and pure, is incapable of fully comprehending the Almighty; that man, the crown of Creation, represents a unity of body and soul; and that the ultimate purpose of human existence is to perform G*d's commandments. These basic principles were the cornerstone on which he subsequently founded the entire system of Chabad philosophy, as described in his great book, Tanya.

When Rabbi Shneur Zalman returned to Vitebsk one and a half years later, as promised, his companions asked him what he had found in Mezherich that was not to be found in Vilna. His answer was, "In Vilna you study the Torah; in Mezherich, the Torah teaches you." What he meant was that in Vilna, a Torah scholar feels proud and self-important about his achievements. In Mezherich, on the other hand, the scholar's "self' is relegated to the background, eclipsed by the dazzling greatness of Torah.

For a number of years, the married couple lived in dire poverty. Finally, in 1767, Rabbi Shneur Zalman was offered the position of preacher in Liozna. From that time on, the authority of Rabbi Shneur Zalman (otherwise known as the Alter or "Old" Rebbe) steadily increased. Three years later, the Maggid of Mezherich entrusted Rabbi Shneur Zalman with the task of re-editing the Shulchan Aruch - the Code of Jewish Law. The main innovation in the resulting work was that it provided a brief outline of the underlying reasons and significance of each law, as well as a selection of practical guidelines gleaned from among the numerous and at times contradictory interpretations offered by the great law-givers, among them the Rambam, the Rosh, and the Beit Yosef. Inaddition, Rabbi Shneur Zalman cited an extensive list of sources and references for every law. This was an enormous task, requiring extraordinary knowledge of the Talmud and practical Halachah. Furthermore, a great deal of decisiveness and self-assurance were needed in order to resolve the thorny issues over which the aforementioned authorities held dissenting opinions.

This new edition of the Shulchan Aruch, except for the first part, was published after Rabbi Shneur Zalman departed from this world. This book has been accepted and acclaimed by the entire Jewish people, not by Chabad Chassidim alone. It is known as the Shulchan Aruch HaRav (the Rabbi's Code of Law).

After Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezherich, left this world, his son Rabbi Avraham (known as the Malach, the "angel") declined the role of Rebbe. Three of the Maggid's most prominent disciples - Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, Rabbi Avraham of Kaliska, and Rabbi Shneur Zalman - separated, each going to a different location with the pledge to spread the Chassidic philosophy wherever possible. Rabbi Shneur Zalman inherited the formidable undertaking of introducing Chassidism to Lithuania, the stronghold of the mitnagdim. Despite all the obstacles, he succeeded in this task. Among other things, he established religious schools for young men with outstanding ability.

His path was fraught with difficulties. During his travels, he was often forced to go into hiding to evade persecution. Once Rabbi Shneur Zalman was invited to a halachic debate against a select group of mitnagdim. To the great disappointment of his adversaries, he astonished everyone present with his extraordinary mastery of the Talmud. In a letter preserved from that time, one of the people present at the debate wrote that after the talk given by Rabbi Shneur Zalman, over four hundred of the most illustrious Torah scholars joined the Chassidic movement, many of them following him to Liozna.

The Rabbi's popularity and admiration for his righteousness and knowledge were so great that the number of people flocking to Liozna grew with each day, until he was compelled to issue "the Liozna rule," limiting the number of visits the Chassidim could pay to their Rebbe.

The Tanya - the Alter Rebbe's major work - was first printed in 1797. Hundreds of handwritten copies had circulated throughout the cities and towns of the Russian empire. However, repeated copying of the book had led to an unacceptable number of errors, so the Alter Rebbe saw the need to print it. At its core, the book is a revised version of the answers given by the Alter Rebbe to the questions asked by Chassidim during personal counseling sessions.

The Tanya fuses together the nigleh ("revealed") aspect of Torah, based primarily on the Talmud, and its sod ("hidden") part, drawing on the Kabbalah: the Zohar, the teachings of the Holy Ari, Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, and other Kabbalists - but it is primarily based on the teachings of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid of Mezherich. The Tanya was written for those seeking and thirsting for knowledge, but not for confused individuals, entangled in the web of philosophy and skepticism, for whom the Rambam had written his famous Moreh Nevuchim (Guide for the Perplexed) six centuries earlier. The Tanya was intended to reach, and did reach, simple and sincere people of unshakeable faith, who were searching for new, better ways to serve the Almighty.

The Tanya (named after the first word of the book), also known as Likutei Amarim (Collected Discourses), presents the substance of Chabad philosophy. As implied by the word "Chabad" (an acronym of the Hebrew words Chochmah - Binah - Da'at (reason - understanding knowledge), this philosophy emphasizes that it is incumbent upon us to use the rational power of the intellect to strive for knowledge of G*d and His entire creation. At the same time, Chabad constantly reminds us of the limitations of human reason, which can never achieve complete understanding of the Creator or fully grasp how the material world was created out of pure spirit. Devotion to the Almighty, based on awe and love, must be preceded by rational awareness of the principle of Permanent Creation (based on the Baal Shem Tov's teaching that the Almighty constantly recreates and sustains the existence of every object and every living creature), as well as the idea of omnipotent Divine Providence. This awareness can and does lead Jews to experience fear and love of G*d, at least at the lowest level of fear and love. All of this does not in any way contradict the concept of the ultimately unknowable nature of G*d.

The Tanya explains in detail the concept, which is of paramount importance, that each Jew possesses two souls: the nefesh elokit (godly soul), which partakes of G*d's essence, and the nefesh bahamit (animal soul). Naturally, the former strives toward virtue, light, holiness. The latter also has the faculties of reason and emotion, and is as capable of striving for positive goals as the godly soul, yet it is equally capable of exercising its base instincts by striving for earthly rewards and pleasures. These two souls wage a constant battle with each other. G*d, true to the principle of free choice, does not intervene in this battle, although He naturally wishes to see the godly soul be victorious, for by conquering the animal soul and raising it to virtue, light and holiness, the nefesh elokit accomplishes the purpose for which it descended into this corporeal world.

People are divided into the righteous, who have totally subdued the animal soul, or even converted its brute power into virtue, and the wrongdoers who are ruled by the animal soul. Inbetween these extremes is the beinoni ("intermediate") person, the actual subject of the entire Tanya, who, though he has never actively violated a commandment, has never succeeded in fully taming his base instincts. An ordinary person is not expected to become a saint, but he is able and required to reach the beinoni level, hence the appeal to do teshuvah - to return to one's source and to remember one's purpose. Universal teshuvah will bring about the coming of Mashiach and the attainment of the ultimate goal of Creation - the establishment of the kingdom of light, goodness, and truth, in which G*d will be a tangible, visible presence.

As mentioned above, the Alter Rebbe's Tanya is a remarkable synthesis of Talmudic knowledge and Kabbalistic teachings. Those who succeed in studying Tanya in depth become permeated with the understanding that there is nothing but the Almighty. The minds of the Rebbe's Chassidim were occupied with the new teachings even while they were engaged in the most mundane chores of daily life. The story is told that Rabbi Binyamin Kletzker, one of the Alter Rebbe' s most devoted Chassidim, was so preoccupied with thoughts about the Creator that while filling out a report on his financial affairs, he wrote in the "total" column: Ein ad milvada ("There is nothing but the Lord!").

The extraordinary popularity of the Alter Rebbe added fuel to the fires of jealousy and enmity. Two years after the publication of the Tanya, he was arrested on charges of treason against the Russian empire. The pretext for the denunciation was the fact that the Rebbe collected funds to support the needy in the Holy Land, which was part of the Turkish Empire at the time. Since Turkey had been at war with Russia for many years, he was accused of abetting an enemy of the czar. The Alter Rebbe was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter-Paul fortress in Petersburg.

Chassidim recount that the Rebbe was arrested in Liozna on a Thursday, put in a horse-drawn carriage, and sent to Petersburg under close guard. The next day, with only a few hours left until the start of Shabbat, the Rebbe asked the officer in charge of the guards to delay the trip until after Shabbat. The officer categorically refused. They continued on their way, but a short time later one of the carriage's axles broke. There was no choice but to stop and send for a blacksmith from the nearest village. Soon the axle was fixed, and the journey resumed. Suddenly, one of the horses collapsed and expired. The guards were gripped by fear and confusion; still, anew, fresh horse was brought instead. However, no matter how hard the horses strained to move the carriage, it would not budge an inch. By then, the officer himself was terrified. He told the Rebbe that they would stop for the night in the nearby village, but the Rebbe refused his offer, worried that they would not reach the village before sunset. Eventually, they pitched camp in the woods by the side of the road. As soon as Shabbat ended, the journey continued without any further mishaps.

At the fortress, despite hours of relentless questioning, the investigators found nothing to substantiate the charges against the Rebbe. As the investigation wore on, the interrogators became increasingly impressed by the Rebbe's extraordinary personality, his brilliance, and his boundless erudition in every area of knowledge. His cell became the site of frequent visits by top government officials. By some accounts, the czar himself paid a visit to the Rebbe. He came incognito, wearing plain clothing, and tried not to do anything that would betray his true identity. Even though the Rebbe had never seen the czar, and photographs did not exist at the time, he recognized him at once and treated him with every honor that the Torah instructs one to exhibit toward a monarch. The royal visitor was fully as impressed as his subjects by this unusual prisoner.

On several occasions, the Rebbe was interrogated at the Senate, situated on the other bank of the Neva River. He was transported by boat, usually at night. During one trip, the Rebbe asked the officer of the guards to stop the boat so that he could recite the blessing for the new moon. The officer flatly refused. "If I wanted to," said the Rebbe, "I could have stopped the boat by myself." True enough, the boat slowed to a stop. The officer was gripped by spine-chilling fear, yet he persisted in his refusal to allow the Rebbe to recite the prayer. Once again, the boat started to move. After momentary reflection, the Rebbe repeated his request. This time the officer agreed, on the condition that the Rebbe gave a written blessing to him and his descendants. The sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, wrote that when he was a child being told this story about the Alter Rebbe, he wondered why the Rebbe had sought the permission of the guards in order to recite the blessing, rather than do so as soon as he had stopped the boat through his supernatural powers. Only later, after Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak had plumbed the depths of Chassidic philosophy, did he realize that the Alter Rebbe needed the guards' assent because the commandments must be observed as part of the natural course of events rather than through the agency of miracles.

Fifty-three days after his arrest, the Rebbe was completely exonerated and released. The joy of his followers was so intense that it affected many Jews who had not been exposed to Chassidim and the Rebbe until then. Many of them saw the hand of G*d in his liberation. Thus the slanderers' intrigues not only failed to bear fruit; they actually backfired, increasing the popularity of the Rebbe and the Chassidic movement tenfold. The 19th of Kislev, the day of the Rebbe' s release, was declared a holiday by Chabad Chassidim, and became known as the "New Year of Chassidism," or the "Holiday of Deliverance."

Nevertheless, the Rebbe's ordeal was far from over. He was arrested again two years later on new fabricated charges, and was forced to defend himself before the czarist court. This time he was allowed to debate one of his accusers, a rabbi from Pinsk. Their polemic was held in Yiddish, and went on for many hours. Naturally, the judges could not understand a single word. When the debate ended, the court told the Rebbe and his opponent to sum up their arguments in written Russian. Meanwhile, Czar Paul was assassinated and succeeded by Alexander I. Shortly after the coronation, the new czar, eager to win the loyalty of his subjects, including the Jews, dismissed all charges against the Rebbe.

The Rebbe did not return to Liozna. He moved to the neighboring town of Liady, intending to establish a new center of Chassidism. He spent the next ten years of his life in Liady. During that period, he invested great effort in improving the living conditions of Jews throughout Russia. One of the primary purposes of his special fund for the needy was to provide aid to Jewish refugees left destitute by the persecutions of 1804, when Jews were expelled from their homes after being accused of selling vodka to the peasants and causing them to stop working.

In 1812, when Napoleon's army invaded Russia, many Jewish leaders, attracted by Napoleon's promises of equality and freedom, and particularly his stated intention to grant the Jews all the rights and freedoms they had yearned for, prayed for the victory of the French. However, the Rebbe could foresee the consequences of this freedom. He saw that if the French won, the economic position of the Jews might improve, but their spiritual condition would suffer. If, on the other hand, the Russians won, the Jews would suffer economically - in fact, they would be persecuted but the Jewish spirit would flourish. The Rebbe therefore supported the czar, doing everything in his power to bring about Napoleon's defeat, for he feared that if Napoleon were victorious, the consequent emancipation of the Jews would lead to mass assimilation.

The Alter Rebbe emphasized that in ethics and in politics, and in everything pertaining to the performance of commandments, reason must rule the heart. Rabbi Shneur Zalman's followers strove to nurture this rational faculty, fostering the power of reason over the emotions, yearnings, and impulses of the heart. One of the youngest disciples of the Alter Rebbe, Rabbi Moshe Maizels, was a person of phenomenal erudition. His accomplishments included fluency in half a dozen languages. During the war between Napoleon and Russia, the French General Staff invited Rabbi Maizels to serve as a translator. The Alter Rebbe enthusiastically supported Rabbi Maizels' decision to accept the offer. By being present at the secret meetings of the French General Staff, Rabbi Maizels would obtain invaluable intelligence for the Russian army.

Eventually, Rabbi Maizels was suspected of espionage. The matter reached the attention of Napoleon himself. The furious emperor burst into a meeting of the General Staff, and rushed at Rabbi Maizels, shouting, "You are a Russian spy!" He then placed his hand on Rabbi Maizels' chest; the Chassid's heart was beating evenly and slowly, and he showed no signs of panic. Napoleon was forced to apologize. Rabbi Maizels later told Rabbi Eizel of Gomel, "Reason's ability to rule the heart saved me from certain death."

The Chassidim say that Napoleon was aware of the Alter Rebbe's spiritual battle against him, which caused him great concern. He was tom between fear of the Rebbe's spiritual power, and an inexplicable fascination with the Rebbe. When the French army reached Liady in August of 1812, Napoleon showed up in person at the Rebbe's home and gave orders to conduct a search. He was looking for the Rebbe's manuscripts, or at least some of his personal possessions. The Rebbe, as he was leaving the house before the arrival of the French troops, had given instructions to destroy everything inside, especially his papers. Infuriated and disappointed, Napoleon left the house empty-handed and had it burnt to the ground. The Rebbe later told his family that in the Musaf prayer read on Rosh Hashanah he saw clear signs of the eventual downfall of Napoleon.

The Rebbe and his family spent five months on the run, escaping the French army as it advanced into Russia. Thus they found themselves in the village of Peny (in the Kursk district). The battlefields were left behind. The journey had been exhausting, and the winter was particularly harsh. The Alter Rebbe passed from this world on Shabbat evening, the 24th of Tevet, 5573 (December 27, 1812).