Every year on the festival of Sukkot, the Rebbe staged the celebration of Simchat Beit Ha'Shoevah - the Rejoicing of the Drawing of Water. (During the Temple Period, Jews would pour water on the altar on Sukkot, instead of the wine used during the rest of the year. The drawing of the water to be used in this ritual was accompanied by great rejoicing. It says in the Talmud that one who never witnessed a Simchat beit ha'shoevah never knew real joy. Chassidic teachings draw a profound philosophic parallel between the water libations and the accompanying intense joy.)

Each night during the eight-day celebration, the Rebbe delivers a discourse that lasts for an hour or two, followed by rejoicing and dancing in the streets. Right after Sukkot, on Shemini Atzeret, hakafot - processions with Torah scrolls - are held at "Seven-Seventy."

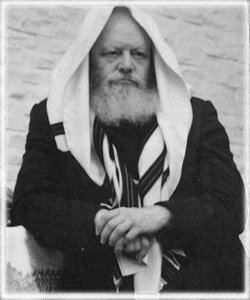

On Sukkot in 5738 (1977), the Rebbe danced as never before. Truly, those who did not witness that night's festivities at the Rebbe's synagogue have never seen what real rejoicing is like! The Rebbe was happy, dancing joyfully with ecstatic abandon. Despite his seventy-five years, the Rebbe was as energetic as a young man. "Seven-Seventy" was filled to overflowing. Thousands of Chassidim were dancing together, their feet moving of their own volition, their eyes shining. The dancing and the singing went on for hours. The Rebbe was focused, in full control of his every step, but his face wore an expression of total bliss - the joy of Torah.

Suddenly the Rebbe's face turned pale. He stopped and slowly lowered himself into a chair. The hearts of the Chassidim skipped a beat; this had never happened before. The Rebbe had never stopped during the hakafot. Everyone's eyes were on the Rebbe. Something was amiss.

A whisper passed through the crowd, "Is there a doctor here?" Several doctors rushed toward the Rebbe. They examined him and found nothing. Still, something was wrong. He was urged to go upstairs to his room and rest a while.

The Rebbe absolutely refused to leave at the height of the hakafot. Out of the question.

The hakafot continued, but the initial joy was gone. The Chassidim were petrified by the thought that the Rebbe might be unwell. The festive mood had been marred by anxiety.

The last hakafah came to an end. The Rebbe rose and walked to his private sukkah adjacent to his office with slow, measured steps. On the way, he instructed the guests, "Do not stop the festivities! Keep dancing!" He entered his sukkah, made kiddush, then settled in his office. Meanwhile, downstairs, the Chassidim went on dancing. Their vigorous singing shook the walls. Yet in the midst of all this revelry, the people's hearts were gripped by fear.

The Rebbe's secretaries were already on the phone, calling the best cardiologists in New York. In the middle of the night the doctors, armed with advanced medical equipment, hurried to "Seven-Seventy." Four doctors examined the Rebbe thoroughly. The Rebbe took an active part in the doctors' discussion, amazing them with his knowledge of cardiology. They could not understand how someone who had never studied medicine could have such deep insight into the intricacies of cardiac function.

The examination revealed that the Rebbe had suffered a serious heart attack. His condition was extremely grave.

"Did the Rebbe moan with pain?" inquired one of the doctors.

"The Rebbe did not utter a sound," replied the secretary.

"That's impossible," said the doctor in disbelief. "He did not cry out, or twist in pain?"

"All the Rebbe did was sit down in a chair," replied the secretary. "No one heard him complain or moan."

"I have to tell you," explained the doctor, "that the Rebbe has gone through agony. The pain is more than anyone can bear. In all my years of experience, I have never seen a patient react to a heart attack in such a manner. This is incredible," muttered the doctor. "I have never seen anything like it."

The doctors decided to inject the Rebbe with a painkiller, but when they asked for the Rebbe's consent, he refused. "There is no need," he said. One of the Chassidim present indignantly confronted the doctor: "Don't you understand that by phrasing the question in that way, you are forcing the Rebbe to answer in the negative? Today is a holiday, and Jewish law stipulates that on a holiday, an injection may be administered only on doctor's orders!"

The doctor, realizing his mistake, turned back to the Rebbe. "Esteemed Rebbe! In my capacity as your physician, I must insist on an injection. This is absolutely essential. Pains of this magnitude can be life threatening." The Rebbe immediately gave his consent.

In the meantime, the doctors had decided that the Rebbe must go to the hospital immediately. His condition was serious, requiring proper equipment and special care.

The Rebbe's voice sounded weaker than usual, but his answer was firm: "I am not going anywhere. I am staying here."

A tense silence fell in the room. One of the doctors appealed to the Rebbe, "Your condition is very dangerous, and you know it. After all, you have demonstrated an excellent knowledge of medicine. This place is not equipped to provide you with the necessary treatment. By remaining here, you endanger your life - that is as clear as day. Only a hospital has everything needed to treat a patient in your condition. Moreover, experienced doctors will be constantly on hand to render their assistance if necessary. You should not remain here under any circumstances. We insist on immediate hospitalization."

"I am not leaving," the Rebbe repeated. "I am staying right here."

A second doctor tried to reason with the Rebbe, to no avail. The Rebbe had made his decision, and nothing could change it.

After a hushed consultation, one of the doctors finally said, "If you do not consent to be hospitalized, we will leave at once and decline any responsibility for the consequences. As experienced specialists, we must warn you that you are putting your life at risk. If you refuse to go to the hospital, we cannot assume responsibility for your life!" At two a.m., the doctors packed up and left. Mere hours after his massive heart attack, the Rebbe was left without medical supervision or treatment.

The Rebbe's secretaries and a number of Chassidim set about bringing medical supplies from the Jewish hospital in Brooklyn to "Seven-Seventy." One of the doctors on the hospital staff helped them find everything necessary. Within an hour, the Rebbe's office was transformed into a hospital room, complete with the most up-to-date medical gadgetry. The same doctor connected the Rebbe to the equipment and remained at his side. At five in the morning, he was shocked to discover that the Rebbe had suffered another heart attack.

The dismayed secretaries began to lose their self-control. They themselves were on the verge of heart attacks. Everyone realized that the Rebbe must be provided with the best medical care possible. What were they to do?

After spending a sleepless night at the Rebbe's bedside, everyone had the same question: "What now?" Then, at about six a.m., one of the secretaries exclaimed suddenly, "Doctor Weiss! Doctor Weiss from Chicago! He is just what we need!"

Doctor Weiss, a cardiologist, was one of the countless Jews who had joined the Chabad movement, and had even visited "Seven-Seventy." While still a young man, he had made a name for himself as a promising, gifted cardiologist. The secretary lost no time in calling Dr. Weiss. At first, the doctor was taken aback - it was a holiday, and making telephone calls on a holiday is permitted only in life and death cases. As soon as he was told about the situation, he curtly said he would be on the next flight to New York, and hung up.

Several hours later, Dr. Weiss was standing at the Rebbe's bedside. After examining the Rebbe, he decreed. "It is difficult to treat the patient under these conditions. Difficult, but not impossible. I will stay here as long as necessary, and I will take care of the Rebbe until he recovers." The Chassidim began the morning prayers. By then, everyone knew that the Rebbe had suffered a severe heart attack, but his instructions had been to continue the hakafot, performing the mitzvah of holiday rejoicing. How could they celebrate when the Rebbe was in such grave danger?

At the same time, a minyan gathered in the Rebbe's room. The Rebbe recited his prayers while lying in bed; he then read the haftarah. The next morning, the Rebbe was already sitting up as he prayed.

All through the second day, the Chassidim were ill at ease. The holiday was drawing to a close. Until then, the Rebbe had never missed leading a farbrengen at the end of Simchat Torah. Then a rumor began to circulate: the Rebbe was going to lead the farbrengen by microphone! The people could not believe their ears! A mere forty-eight hours ago, the Rebbe had suffered a massive heart attack! How could he possibly be well enough to talk, let alone deliver a discourse on Torah?