How does a Rebbe come into being? What is the source of his supernatural abilities, his spiritual power, his faculty for making critical decisions and guiding others? An exhaustive answer to these and similar questions lies beyond human capacity.

Some people are gifted with exceptional genius.

Some young men, raised and educated in their parents' home, possess outstanding spiritual qualities. However, these factors are clearly not sufficient to form a Rebbe. Numerous Torah scholars immerse themselves in the depths of the halachah, yet at most influence a narrow circle of pupils and close friends. A Rebbe must possess a greatness that defies all imagination, a spirit whose power sweeps away every obstacle. Most importantly, a Rebbe must possess boundless love for every Jew. This love spreads from heart to heart; it knows no boundaries or limitations; it is unconditional, beyond calculation; it is akin to the love of a father for his son, yet multiplied a hundredfold.

No one has been able to describe the precise mechanism of the Lubavitcher Rebbe's influence, to capture the enigmatic essence of his personality, the unique qualities that raise him to usually unattainable heights. Despite our attempts to analyze the elements that make up the extraordinary image of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, we do not presume to have exhaustive or accurate answers.

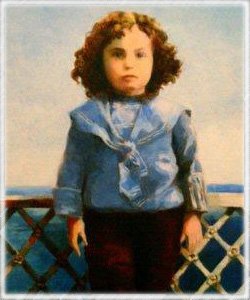

Can it be that when he was born, on the 11th of Nisan, 5662 (1902), there were people in Nikolaev who foresaw the great future in store for the newborn baby? Is it conceivable that even then, someone's inner vision foretold that the baby was destined to become the leader of the entire Jewish people? Those accustomed to relying exclusively on their rational mind will dismiss the idea as preposterous, yet it is true. On the day of the birth, Rebbe Shalom Dov Ber sent no less than six (!) telegrams containing detailed inquiries and instructions concerning the baby. Following these instructions, his mother, Rebbetzin Chana, washed her own and the baby's hands prior to each feeding. Thus from the moment of his birth, the Rebbe did not eat a single meal without washing his hands. Even the most religious families usually teach their children to observe this commandment only from the age of three.

The circumcision ceremony was held during the Pesach holiday. The boy was named Menachem Mendel, after his great, great, great-grandfather, the Tzemach Tzedek. The day of the circumcision was the baby's father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak's twenty-fourth birthday. During the festive meal following the ceremony, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, a great expert in the Kabbalah, talked about the significant connection between birthday and circumcision, according to the teachings of the Kabbalah.

By the age of two, Menachem Mendel was already able to ask the four traditional questions during the Pesach Seder. Six months later, he could pray as fluently as an adult. Once, when Jews had gathered in his father's house for the evening prayer, Menachem Mendel, then two and a half, jumped out of his little bed in the next room and joined them in prayer. The Rebbetzin, afraid of the evil eye, carried the boy back.

When the child turned three, he was brought to a cheder, as was the custom. A group of three-year-old boys sat around the table at the home of the melamed, who was teaching them the Hebrew alphabet and other Torah basics that lie within the grasp of a three-year-old child. Menachem Mendel's melamed, Rabbi Zalman Vilenkin, quickly saw that the boy had nothing to learn at the cheder, and began to give him private lessons. (Many years later, Rabbi Zalman Vilenkin managed to flee the Soviet Union and visited the Rebbe, who treated his former teacher with the utmost respect and honor, as prescribed by halachah.)

The failed Russian revolution of 1905 sparked a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms. When Menachem Mendel was four and a half, one such pogrom took place in Nikolaev, where his family was living. The Jews looked for any hiding place. Once such shelter, which Menachem Mendel's family shared with others, was filled with babies and small children. They were wailing in fright, creating a dangerous threat of discovery. It was young Mendel, little more than a toddler himself, who immediately grasped the gravity of the situation and started going from baby to baby, calming them with a soothing word, a soft hand, or a candy. He continued doing this until the danger passed.

When Menachem Mendel was five, the Schneerson family moved to Yekaterinoslav, now Dnepropetrovsk, where his father was appointed Chief Rabbi of the city. The anti-Jewish riots had not yet abated. The Yekaterinoslav community, among the largest and most prominent communities in the Ukraine, needed and found in Rabbi Levi Yitzchak a leader of the highest caliber.

The rabbi had a spacious house. Directly off the entrance there was a large hall, where the Chassidim would gather for lessons and prayers. Here they sat for many hours around a long table, listening to the words of their rabbi. Adjacent to the large hall were the rooms of the three sons Menachem Mendel and his two younger brothers, Dov Ber and Israel Aryeh Leib. (Rabbi Dov Ber was murdered by the Nazis in Europe in 1944; Rabbi Israel Aryeh Leib, an outstanding mathematician, settled in Israel, married and had a daughter; later the family moved to London, where he taught mathematics at a university; he passed away suddenly in 1952.) Each brother had in his room a complete set of the Talmud. At that time, this was highly uncommon; the Talmud was very expensive.

Word of the extraordinary abilities, diligence and perseverance of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson's three sons spread through Yekaterinoslav. The eldest son was recognized as the most capable of the three, yet his two brothers did not lag far behind. It was obvious to everyone that a regular yeshiva had nothing to teach them. They studied the Torah on their own, under their father's guidance; in addition, they learned the secular sciences with the help of private tutors. (One of these tutors was Israel Ben Yehuda, who became Israel's minister of internal affairs many years later.) Before long, it became clear that the private tutors also had nothing more to teach the children; their students had surpassed them in knowledge.

Thus the Schneerson brothers taught themselves. Naturally, they emphasized learning the Torah, but they also studied philosophy, mathematics, languages, physics, and social sciences. Menachem Mendel was particularly interested in astronomy.

The boys were both persistent and enthusiastic in their studies. They spent countless hours learning, from early morning to late night. Menachem Mendel differed from his brothers and other children. He had no spare time left for socializing with friends; even in his early childhood, no one ever saw him playing children's games or making mischief. He was always focused, serious and taciturn like an adult, even though his house was filled with events and commotion. After all, this was the home of the city's chief rabbi, a home open to everyone, where guests were always assured of a warm and loving welcome. Yet, even in the midst of all the noise and commotion, Menachem Mendel was able to devote his full attention to his studies.

There are numerous eyewitness accounts of his extraordinary abilities, which indicated a great future even then. Once, when still quite young, the boy and his mother, Rebbetzin Chana, went for a walk along the river embankment. Suddenly the weather changed; a strong wind began to blow and large waves rolled in. The Rebbetzin realized that her son was gone. She began to look for him, and noticed that a crowd of people had gathered nearby. Coming closer, she saw a boy of about four in the center of the crowd, frightened and soaked from head to toe. The boy's mother was saying in a voice choked with emotion, "My child fell into the water and almost drowned. Then an older boy - I've never seen him before - jumped in without a moment's hesitation and saved my child!" Before the Rebbetzin had time to feel alarmed, she saw nine-year-old Menachem Mendel coming back, soaking wet and silent.

By the age of twelve, Menachem Mendel was already part of the inner circle of his Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak. Once the Rebbe had a visit from Professor Barchenko, a prominent Russian scientist. He told the Rebbe that he had heard about certain mysterious powers associated with the Star of David, and that he wished to learn about the secrets of this Jewish symbol.

"Let me ask my 'education minister,'" said the Rebbe. He summoned Menachem Mendel and asked him to inquire into the subject of the Star of David from the standpoints of Kabbalah and contemporary science. Three months later, Menachem Mendel presented the Rebbe with a thick notebook containing the results of his research. Naturally, all the work had been done as if incidentally, with minimal expenditure of time and effort. His main occupation remained the study of Torah.

Menachem Mendel was twelve years old when the First World War broke out. The war sent floods of refugees streaming from Poland into the interior of Russia. Many arrived in Yekaterinoslav; some of them found refuge in the rabbi's home. The house was in turmoil, yet Menachem Mendel continued to behave as if nothing out of the ordinary was happening. All the commotion stopped at the door to his room. Nothing could distract him from his studies. Frequently his father joined him in study sessions that went on until dawn. After that, the boy would snatch an hour or two of sleep before resuming his studies. His entire being was devoted to mastering the Torah, the Talmud, and Chassidic teachings. By the time he reached bar mitzvah age, he knew the entire Talmud by heart - complete with Rashi's commentaries. Somewhere along the way, he had also mastered the secular sciences. What an ordinary, even highly gifted student required two or three months to learn, Menachem Mendel learned in a day or two.

According to some accounts, during a stay at the Petersburg home of his relative, Rabbi Gur Aryeh, Menachem Mendel paid several visits to the famous Pulkovsky astronomical observatory.

When Menachem Mendel was sixteen, he told Yeshayahu Sher, one of the young men who frequented the rabbi's home that, according to his calculations, a solar eclipse was to take place at a certain hour on the afternoon of February 25th of that year. (This man, rather advanced in years, presently resides in Rechovot, Israel; he related this story and the next.) Rumors of this prediction spread through the city. Everyone knew that the word of Menachem Mendel could be trusted. Many inquisitive people prepared pieces of tinted glass in order to observe this fairly infrequent phenomenon. The designated day arrived. As the specified hour drew near, everyone took up his observation post - yet the sun continued to shine as before. The disappointed would-be astronomers went home.

Next day, Yeshayahu came to Schneerson's home. "There was no solar eclipse yesterday," he pointed out cautiously.

"Oh yes there was!" replied Menachem Mendel. "Look, we all stood there and watched the sun, but it remained as full and round as always."

"And I am telling you," parried Menachem Mendel with absolute conviction, "that there was a solar eclipse. My calculations are totally accurate and irrefutable!"

A few days later everyone knew what had happened. The next issue of the Niva magazine ran a long article about the recent solar eclipse. The article mentioned the scientific centers in various areas of the country that had observed the eclipse; all the areas were far removed from Yekaterinoslav.

Several weeks later, Yeshayahu visited the Schneersons again. At the time, he was studying mathematics with an engineer by the name of Ostrovsky. Once he told his teacher about the extraordinary mathematical gifts of the Schneerson brothers. "Let's do an experiment," proposed Ostrovsky. "Here is an equation. If these friends of yours manage to solve it, I will publicize the fact in university circles." Yeshayahu took the piece of paper with the equation to the Schneerson brothers. All three armed themselves with pencils and paper and sat down to work. Several hours later all three had solved the problem. Yeshayahu rushed to the engineer, who could not believe his eyes. All three solutions were correct, but Menachem Mendel had arrived at his in the shortest and most elegant fashion.

That same year, the dean of mathematics at the city's recently founded university paid the Schneersons a visit. Having heard about Menachem Mendel's genius, he presented the boy with a mathematical problem, giving him three days to solve it. Before leaving, the dean stopped to talk with the rabbi. Half an hour later, Menachem Mendel handed the solved problem to the astounded dean. He was certain that the boy was playing some kind of a joke on him; nevertheless, he stuck the piece of paper into his pocket.

At two in the morning, the rabbi's telephone rang. It was the dean. "I cannot believe my eyes," he said in a voice filled with disbelief. "The solution is correct! An experienced professional mathematician would take at least three days to solve this problem. Your son did it in thirty minutes. I simply could not force myself to wait until morning. I am calling at this late hour to express my admiration."

Menachem Mendel mastered English, Italian, German, French, and a number of other languages on his own. Once he decided to learn a language, he would arm himself with dictionaries and grammar textbooks, emerging some three weeks later with knowledge of the language.

During the First World War, an epidemic of typhoid fever broke out in Europe, claiming countless victims. The dread of contagion was so great that many of the sick were abandoned to face their fate alone. Eventually, the epidemic reached Yekaterinoslav. The city was gripped by fear.

Young Menachem Mendel, who had spent almost all his life pouring over books, avoiding friends or anything that could disrupt his studies, decided that circumstances demanded that he put a temporary halt to learning. Instead, he resolved to help the sick, undeterred by all the exhortations and warnings. His love for human beings did not permit him to stand idly by and watch his fellow humans die. Day after day, he visited the homes of sick Jews, bringing medicines to some, food to others, or simply sitting by the bedside of a sick man, listening to his sighs. With patients learned in the Torah, he discussed its teachings. He spent days and nights in this way, until he himself became infected. Though confined to bed, burning with fever, his life in danger, he continued to utter words of wisdom from the Zohar. His body was bedridden, but his spirit was soaring high through heavenly spheres, all the way to the highest spiritual realm, called Atzilut. Listening closely to his words, one could perceive that even in his delirium he was talking about the purpose of creation, the role of mankind, and many other sublime topics.

The crisis passed, and Menachem Mendel began to recover. Throughout the entire period until he was fully recovered, he continued to recite Torah from memory.

The young man was obviously brilliant. The only one who remained unimpressed by his absolutely phenomenal abilities was Menachem Mendel himself. He was reserved, taciturn and shy, shunning society. The only day of the year when he let his emotional guard down was the holiday of Simchat Torah. Then his unfettered joy infected all around him. With closed eyes, as if transported by the melody, he would sing the tunes of the Alter Rebbe and other Chassidic leaders. In the intimate circle of Chassidim, holding the Torah scrolls, he would lose himself in an ecstatic, endless dance that lasted until he was totally exhausted. At those times, he could hardly be recognized as the bashful, retiring youth who spent his entire time in study.

|