Five thousand people stand in a crushing throng in a densely packed room, filled to bursting. Venerable elders stand side by side with beardless youth. Men wearing the traditional black coats squeeze next to longhaired hippies who may have donned a yarmulke for the first time in their lives a moment before entering the hall.

Here everyone is equal: those who belong to Chabad and those who do not, the deeply religious and those who have not yet begun to observe the commandments, the rich and the poor. All of them are overshadowed by one single figure - the Rebbe.

A farbrengen is a special occasion, during which the Rebbe talks to Chabad Chassidim and anyone else who wishes to listen. Farbrengens are held every Shabbat, on holidays, and on special dates on the Chabad calendar such as the 19th of Kislev (the "Chassidic New Year"). If a farbrengen is held on an ordinary day, it is broadcast to the entire world on radio and television. Chabadniks the world over - in Israel, France, Australia and Brazil, and recently in Moscow as well - have an opportunity to see and hear the Rebbe as if they were attending the farbrengen at "SevenSeventy." The farbrengens are also broadcast on American cable TV.

As a rule, the Shabbat farbrengens start at 1:30 p.m., and last three, four, five, six hours, and sometimes even longer.

On a Saturday morning when the Rebbe decides to hold a farbrengen word spreads through the hall by word of mouth, and all plans are put on hold. The women know that their family will eat the cholent and kugel only in the evening, after the final Shabbat prayer.

By one o'clock, the hall is filled to capacity. The crowding is unimaginable. People squeeze as close as possible to the dais where the Rebbe will sit, surrounded by the most elderly and respected Chassidim and guests. The people are packed together like sardines, yet more keep arriving, and, strangely, everyone manages to find a place, some closer, some further away.

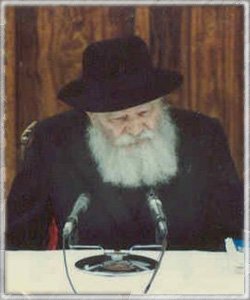

At one-thirty, everyone breaks into a Chassidic melody. The Rebbe comes in. With brisk steps, he ascends the dais, sits in his red velvet chair, recites a blessing over the wine, and thousands of people answer, "Amen!" In some mysterious fashion, numerous bottles of wine materialize among the thousands of guests. The wine is poured into small glasses. Now everyone is looking at the Rebbe, trying to catch his eye. They are all waiting for the moment when the Rebbe will look at them personally. The Rebbe looks around at the crowd and, noting a man who has raised his glass toward him, nods his head and says, "L'chaim velivracha!" "To life and to blessing!" Then the lucky man drinks the wine, and the warmth radiating from the Rebbe' s eyes thaws his heart.

Some minutes later, the Chassidim sense, from signs invisible to outsiders, that the Rebbe wishes to speak, and in an instant the noise turns into absolute silence. The Rebbe begins to talk. The order of his speech is more or less constant; the Rebbe discusses the current events as seen in the light of Torah, the weekly Torah chapter or the meaning of the festival, quoting verbatim countless passages from the Torah, the Talmud, Rashi, the Zohar, Rambam's Mishneh Torah, Chassidic works and commentaries by other sages. In the summer he includes the appropriate chapter of Pirke Avot. The Rebbe elucidates difficult points, examines the issues from every possible angle, and proposes various theses and antitheses, until suddenly the lengthy and fascinating discourse resolves itself in a brilliant synthesis. Next he quotes from the innermost depths of Torah as explored in Chassidism. At the end, the Rebbe offers practical conclusions and instructions based on his discourse, for the Torah says that action is the main point. The final words of the discourse are almost always devoted to the subject of Mashiach, explanations of how everything, especially deeds, may help hasten the arrival of Mashiach, and blessings expressing the hope that this would happen in the near future.

The Rebbe cites countless sources. In the course of a single farbrengen he may quote hundreds of passages from the Torah, the Talmud, commentaries by Rashi, the Rambam, and others, the Kabbalah, and every other possible Jewish thinker. He does not resort to notes to help him recall a quotation or the outline of his speech! An ordinary lecturer brings a pile of papers to his lecture, so as not to forget something essential, and usually deals with a single topic.

The Rebbe, in contrast, discusses dozens of topics at once, quoting verbatim from hundreds of sources for hours on end - and this is all done from memory!

The wife of a famous contemporary writer described the Rebbe's speaking style: "My husband frequently lectures, and is an exceptional speaker. When he speaks, the world ceases to exist for him. He hears only his own voice, sees his own gestures, and overflows with pathos. With the Rebbe, it is completely different. He sees, hears and senses everything that goes on among the five thousand listeners. Each listener, even young children, feels embraced by the Rebbe's concern. This makes all the difference."

The Rebbe's speech lasts anywhere from thirty minutes to an hour, occasionally even longer. Then the singing begins anew. Glasses of wine are raised again, and hundreds of eyes strain once again to catch the Rebbe's eye. He peers into the crowd, nodding now to one person, now to another, while his lips whisper "L'chaim velivracha." The people, meanwhile, continue singing, with the Rebbe often joining in or conducting the rhythm of the music. At those times, the song swells to a new intensity, and the song rises to heaven. Once again the Rebbe gives a signal visible only to the initiated. The congregation instantly falls silent, and the Rebbe continues to speak. All eyes are focused on him. The people listen with bated breath. Even after two, three, or four hours, these thousands of people, many standing on their feet throughout (including some who have only enough room for one leg), drink in his words as if he has only been speaking for a minute.

Each word uttered by the Rebbe is imbued with profound meaning. Even the tiniest nuance is important. Does everyone understand his discourse? Hardly. Certainly a few gifted yeshiva students and venerable Torah scholars understand everything. Many of those present follow the essence of his speech; some grasp certain elements only; and some understand nothing - nothing at all. However, they too listen and concentrate as if comprehending every word. The atmosphere of holiness and spiritual elation holds them enthralled. Each interpretation contains inexhaustible depth, and each person understands it in accordance with his abilities and level of knowledge.

Everyone who has had the privilege of attending a farbrengen - even gentiles - immediately senses that this place is unique, sacred, a world far removed from everything on the outside, beyond the walls of "Seven-Seventy." This world resounds with G*d's living words, which are the highest reality. Thus gaining entry into this world can be a vital step in one's life. Even if his reason did not understand a single word, his heart can feel that he was exactly where he should be.

The Rebbe does not rely on techniques commonly used by other speakers. He very rarely raises his voice or gesticulates to emphasize his thoughts. Throughout the entire farbrengen, the Rebbe's hands remain under the table (except for the moments when he claps to encourage the singers). However, the Rebbe's face and eyes speak volumes to all those present at the farbrengen. The famous artist, Hendel Liberman, of blessed memory, whose works are permeated with the magical fairy tale mood of a Jewish shtetl, frequented the farbrengens even though, by his own admission, he could not understand a word of what was being said. "I learn from the Rebbe's face," he would say. "I study his face all the time, and that is my school."

The Rebbe can speak for up to five hours without tiring, barely touching any food or drink. He teaches for the entire duration of the farbrengen, interrupted only by intervals of singing, yet he does not show the slightest sign of tiredness. His voice, like an inexhaustible spring, remains fresh and pure.

All of the Rebbe's farbrengens held on weekdays are recorded and published in the form of collected speeches or separate brochures. On Shabbat and holidays, when it is forbidden to record, several men stand close to the Rebbe and focus all their attention on his speech. They are the chozrim (the "repeaters"), who have exceptional memories. During the brief interludes of singing, the chozrim mentally repeat everything the Rebbe said. Their job is to memorize the speeches that the Rebbe makes on Shabbat. At the end of Shabbat, they reconstruct the entire speech on paper word for word!

A perfect system is in place to ensure quick, precise reproduction of the Rebbe' s discourses. People record the Rebbe's speeches, translate them into different languages, print and distribute them throughout the world. This process is accomplished with truly staggering speed. For example, a discourse delivered by the Rebbe on the day before Yom Kippur is published before the holiday actually starts!

Every farbrengen is stamped with the seal of holiness, but farbrengens held on memorable dates in the Chassidic calendar are the holy of holies! People converge from every comer of the world to take part in such a farbrengen. On those days, headphones provide simultaneous translation into many languages for those who do not understand Yiddish. The Rebbe' s speech may be heard in Hebrew, English, French, Spanish and Russian. These farbrengens start at nine-thirty p.m., but three hours earlier the hall is already so packed that it seems impossible to enter, yet people continue to pour in. The women's section is also filled to bursting. People's hearts overflow with festive elation and the sense of holiness, while the mixture of voices exchanging whispers in different languages brings home the true meaning of the phrase from psalms, shevet achim gam yachad ("brethren dwelling together in unity."). The farbrengen continues far into the night, but it never occurs to anyone to look at a watch. In addition to discussing various topics related to the Torah, the Rebbe uses the farbrengen to issue practical instructions that are immediately circulated to his Chassidim throughout the world. For example, during one farbrengen the Rebbe talked about the importance of attaching kosher mezuzahs on the doors of all maternity wards in American hospitals, since Jewish women also give birth in those hospitals, and even one Jewish birth a year justifies installing the mezuzahs. Several hours later, groups of Lubavitcher Chassidim were already touring the hospitals and attaching mezuzahs wherever they were missing, as well as checking those already in place.

Though the Rebbe rarely raises his voice, there are a few exceptions: the Rebbe becomes very emotional when speaking about the galut. "How long?" he cries with tears in his eyes. "How long shall we live in exile, while Mashiach tarries?" This sends a message to every Jew that he or she is personally responsible for hastening the arrival of Mashiach by intense Torah study and observance of the commandments, particularly the one that requires loving the people of Israel and striving to attain complete unity among all Jews. The Rebbe reiterates this theme tirelessly at every farbrengen, time after time, week after week. Again and again, he stresses the point that every individual Jew has the potential to hasten the coming of Mashiach.

The Rebbe also uses farbrengens to express his views on various Jewish issues, both global and local. The farbrengens form one of the major links in the chain that ties the Rebbe to his Chassidim and the rest of the world. It is no wonder, therefore, that a Chabadnik will unhesitatingly abandon all his plans, no matter how important, so as not to miss a farbrengen. People are willing to incur huge debts and travel from the end of the world to visit the Rebbe. Here they receive their spiritual nourishment; here they find the meaning of their entire existence.

Chabadniks living in Israel have particularly distinct memories of farbrengens devoted to events that took place in Israel at various historical crossroads. No one is likely to forget the farbrengen held on the eve of the Six Day War. Some of the yeshiva students who had come from abroad to study in Israel were set to leave the country as soon as it became clear that war was about to break out. In the course of the farbrengen, the Rebbe instructed all of his students in Israel to stay put, predicting that the Jewish people would achieve a brilliant lightning victory, and that the students were not in any danger.

Another memorable farbrengen was devoted to passages from the Book of Esther. With extraordinary emotion, the Rebbe quoted the following words: "For the fear of the Jews fell upon all people," and "no man could withstand them." Then he fell into a long silence before he continued his discourse. Later it was discovered that just as the Rebbe was citing these passages from the Book of Esther, Palestinian terrorists were attempting to hijack an Israeli plane.

The farbrengens were not always the mass event that they are now. When the Rebbe's "court" was significantly smaller, and the number of farbrengen participants was limited to a smaller circle, the Rebbe was able to address each participant in person, not only mentally but also physically. A man named Abraham Herzman used to attend farbrengens despite the fact that he kept his store open on Shabbat. The Rebbe was aware of that, and from time to time tried to persuade him to stop violating Shabbat. The Rebbe voiced his objections in Italian, which was this man's mother tongue, incomprehensible to most of the congregants. One Shabbat, the shop owner's resistance finally melted; he came up to the dais, took out the keys to his store, and said with tears in his eyes, "Rebbe, here are the keys to my store. From now on they are yours." The Rebbe took the keys, his face lit by the special smile that can only be imagined by those who have seen the Rebbe in person. Then he handed the keys back to the man and said, "The store is yours, but only six days a week." From that day onward, Abraham Herzman has been meticulous in his Shabbat observance.

|