|

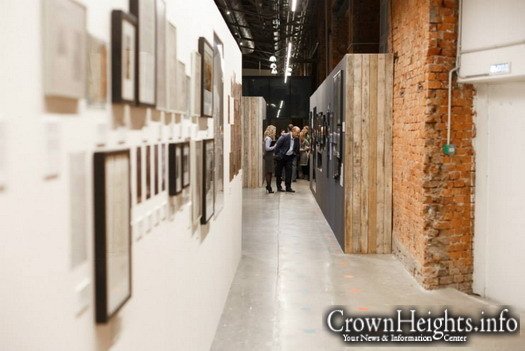

Walk into what was once a Moscow bus station and you’ve stepped into what’s not merely an institution of “living history” but one of “interactive history” – a place where one can go back in time not by the simple act of looking at the past but by actually taking part in those times in the present moment.

This once upon a time beleaguered bus station (once and now again an architectural masterpiece in its own right), in Moscow, has become the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center. It is the world’s largest museum dedicated to telling the story of Jewry; in this case, Russian Jewry.

Judaism, Jewish culture and Jewish history have been intertwined with the story of Russia since the country’s beginnings. From the days of the Czars through the Soviet era and up through the current time, there was no one particular place where the story of Russia’s Jews and the part they played in the building of the nation could be told.

Parts of the story lay in history books, of course. Other parts in poems and novels, in films, in stories passed from one generation to another, in memories of Mother Russia held by Jews who immigrated to other lands, or who remained behind in a land that sometimes challenged them and where they also flourished greatly. And where, today, there’s a Jewish renaissance of sorts taking place as Russia’s Jews play a prominent role in the life of the nation and where thousands of tourists from Israel, indeed Jews from all over the world, come to visit and remember a past whose vibrancy called out to museum founders to be celebrated. And they see, too, that this Museum not only celebrates the history of Russian Jews but stands as a beacon representing a bright future.

“It was around 2000, perhaps 2001 that the idea of a museum devoted to telling the story of Russia’s Jews began formulating in the minds of those who envisioned this museum,” says Mr. Baruch Gorin, the Museum’s director. “One of the miracles of this museum was being given this building to house it.”

As the vision for the museum took shape, Rabbi Berel Lazar told President Putin that he wanted to have such a museum in Russia. “President Putin asked why it was so important to have one,” says Gorin, “and it was pointed out to him that major cities around the world had museums devoted to Jewish history – all too often the darker side of that history.” A museum was needed to tell the intricate saga of Russia’s Jews and the vital role they played and still play in the story of Russia.

How did President Putin react? “He was intrigued by the idea,” Gorin says. “’If it’s to be,’” the President said, ‘it has to be the best museum of its kind in the world.’” He pledged a month’s worth of his own salary to help get the effort started. Individual and corporate donors followed suit and made what we have here a reality.”

Visitors, and there’s been over 600,000 in the few years since the Museum opened its doors, get to “step” (for example) into a virtual reality version of Odessa about the time that the 19th century turned into the 20th.

Touch a button and suddenly you are “within” the café … hearing the talk amongst the Jewish patrons, getting a chance to “speak” with the famous writers who once frequented such cafes for sweet tea from samovars and discussions about Bolshevism, about Zionism. There’s a newspaper on a café table whose contents suddenly become “fresh news” in the eyes of a beholder who might never had previously thought he could go back in time like this.

“There is no such thing as Russia without the Jews, no Russian past without a Jewish past.” Gorin points out.

Or tap on a Torah in an interactive display and listen as a cantor begins to sing its holy words. Or, take part in the texture of life as it was lived amongst the urban intelligentsia or as it was lived by those who inhabited rural shetyls. As the museum director says, “When you touch the challah on the table in the exhibit, you become part of the family’s Shabbat dinner. You have to touch the challah, though …. the exhibit does not work without you initiating it.”

This is a place where one can not only discover or rediscover roots but also follow the flourishing and flowering of Jewish life that continues through the present day. As the New York Times reported when the Museum opened in 2012: “Exhibitions are divided chronologically, helping visitors to understand the life of Jewish communities as they travelled across medieval Europe, settling in shtetls before moving to the cities. The role of Russian Jewry in public life in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries is particularly well presented as is the fate of Soviet Jews and the role of Jewish soldiers during World War II … Those expecting to find just a stark representation of pogroms, holocaust, hardships and suffering will be pleasantly surprised to find Russian Jewish history presented as something much more complex, filled with both struggles and achievements.”

The idea behind this museum, says Gorin, is that “Jewish history does not work without you.” What he means is that every person who comes to the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center is not a mere visitor but a participant. As Gorin, says: “You are inside history here at the Museum, not outside of it looking in.”

The Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center is visionary in scope and execution, brilliantly devoted to Jewish life – with an emphasis on both words.

|